Keeping creativity on rails

Experiments balancing creativity and deterministic code generation

Introduction

In my last post, I explored deterministic code generation using AI. In these early days of AI-assisted development, organizations face two risks:

stifling AI creativity in the fight against hallucinations, or

falling prey to “vibe coding”—essentially hoping a roomful of infinite monkeys will eventually produce perfect code.

Striking a “creativity on rails” balance requires understanding how changes to a code-generating LLM’s inputs control different aspects of its output.

In this follow-up, I’ll walk through experiments I ran to see how prompt and context specificity affect deterministic code generation.

Up front: these are simple tests exploring a spectrum of specificity typically used for proofs of concept and MVPs, not production projects. See my “Next steps” section at the end for additional tests that address challenges specific to larger, production-quality codebases.

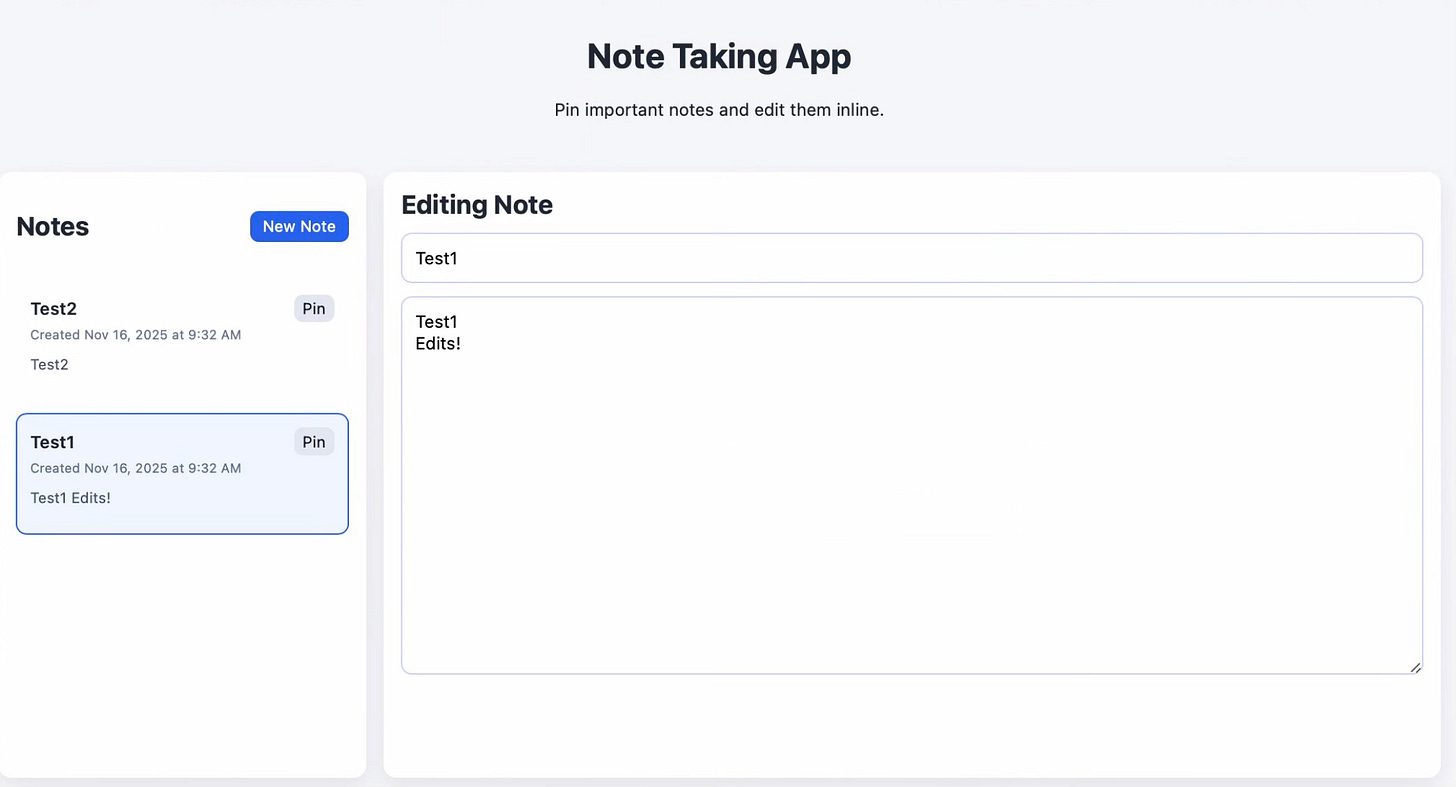

What we’re building

For each test build in this experiment, the goal was the same: build a simple note-taking app. I chose this because:

I wanted a multi-component, single-page tool. At their simplest, note-taking apps have a list of notes and a text box for entry, all on one page.

There’s variety in how note-taking apps can be laid out visually (as seen in the market today), so I hoped we’d see UI variety increase as prompt specificity decreased. Spoiler alert: this assumption turned out to be true.

Diversity in UI component look and feel would likely translate to at least superficial differences in the underlying codebase, which could be examined.

Complexity divided into tiers

To test how prompt and context specificity affect code generation, I created 5 tiers, each one more specific than the last.

Tier 0: Intent only—an intentionally vague prompt. Pure vibe coding.

Tier 1: Requirements—more specific functional requirements, but other decisions explicitly left to the LLM. This is where I start specifying basics like “use React and TypeScript.”

Tier 2: Requirements + architecture guidance—tighter functional requirements, including data model and data flow.

Tier 3: Requirements + architecture + technical specs—locking down data structures and file names.

Tier 4: Full single-file PRD with all files, functions, and states explicitly defined.

At each tier, I used Codex to generate a note-taking app twice. My expectation was that I would see fewer differences per generation as I went up successive tiers.

A note about these prompts

I used LLMs to generate the prompts and PRDs for each tier, just as I’ve done for other projects on this blog. I chose this approach because meta prompting—prompting to generate prompts—has become a well-established technique in AI-assisted software development. Generating these prompts with LLM support helped ensure that specificity increased systematically from tier to tier.

That said, if I ran this experiment again, I’d remove the explicit lists of features that the LLM is free to customize. Prompting “it’s okay to be creative here” probably yields a different result than simply leaving those features out entirely.

All prompt input, two generative outputs per tier, and an LLM-based comparison of outputs at each tier is available here:

Deterministic code experiments repo

Helper script to do project comparison

As mentioned, I wanted the LLM to review the code output because I assumed it would catch differences I might miss. The script that runs the LLM-based comparison of two projects is included in the GitHub repo.

I also included the prompt to generate the script. Looking back, I should have made that prompt more specific. The LLM’s comparative output varies widely in detail across the tier directories—a direct result of the script generation prompt being too loose.

This touches on another subject I’m exploring in a project I hope to write about next month. These initial determinism vs. creativity experiments appeal to me because I’m building apps that perform tasks with a backend LLM. Optimizing LLM output for those tasks often comes down to tuning the balance between determinism and creativity.

But for now, onto the test results.

Tier 0

The prompt for this tier was so short that I can include it here:

Build a simple note‑taking app using React.

The app should allow users to create and view notes.

Do whatever you think is best for the project structure, UI, and state management.

The UI between the two builds diverges, not just in style but in functionality. One generation included a filter feature; the other didn’t.

Only one build included persistent storage. This shows how different two outputs can be—and how those differences translate to substantial variations in functionality and quality.

The prompt explicitly told Codex it was building a “note-taking app,” so it understood the task. And persistent storage is a standard feature in note-taking apps. Why use the app if you can’t save your notes?

Even “simple” note-taking apps include persistent storage. Yet 50% of the time, the LLM failed to include it!

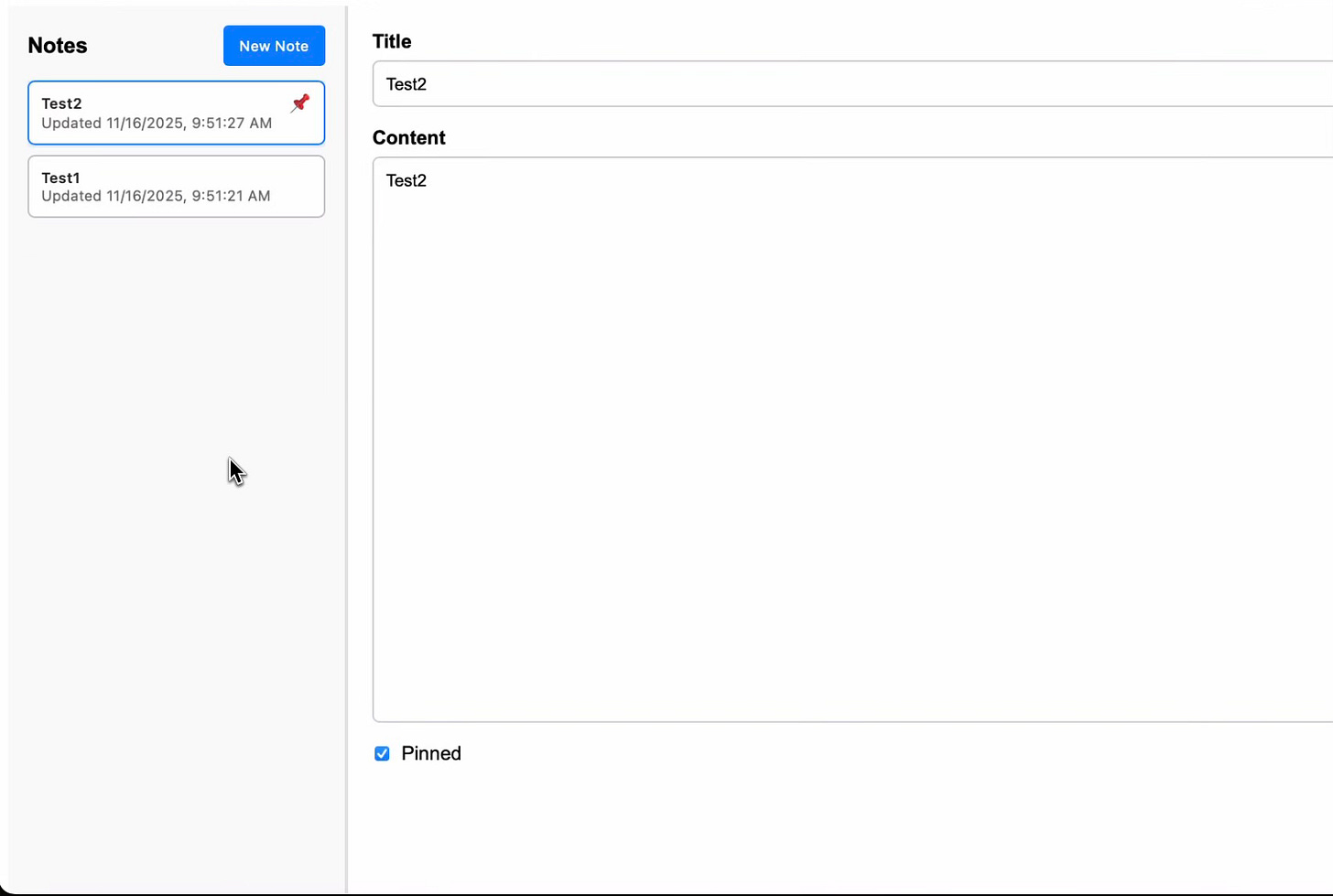

Tier 1

The prompt for tier 1 has two short sections: one detailing required features and another specifying what Codex can decide on its own.

The UI for tier 1 still differed about as widely as it did for tier 0. Also, as with tier 0, only one of the two generated apps supported persistent storage.

The source code for the two apps created at tier 1 diverged as much—or possibly more—than tier 0. One instance had significantly more files than the other, primarily because of how Codex divided the source code across files.

Tier 2

All four apps from tiers 0 and 1 worked on the first try. I queried Codex with my prompt, it generated code, and the app ran successfully without any debugging or updates.

Starting at tier 2, none of the generated apps worked without additional prompts. The package.json file—which contains project requirements and dependencies—wasn’t being generated.

This was an unexpected consequence of making prompts more deterministic. Because I didn’t explicitly ask for package.json to be created and my prompt restricted Codex’s creativity, the file wasn’t created. In this case, “creativity” means knowing to create mandatory files without being explicitly told to do so.

The UI is starting to converge. This is the first pair of generated apps with a nearly identical layout. This matters because while my tier 2 prompt includes specific sections on app requirements and “UI&Flow,” the final section still lets Codex decide “exact layout and styling.” My conclusion: even though Codex was nominally free to design the UI however it wanted, the tightening constraints elsewhere in the prompt narrowed its generative reasoning to a semantic space where note-taking apps “just look like that.”

Of course, this is a small sample set. Running many more iterations would help reveal the variety of note-taking app styles within the more concentrated semantic space reached by tier 2’s prompt.

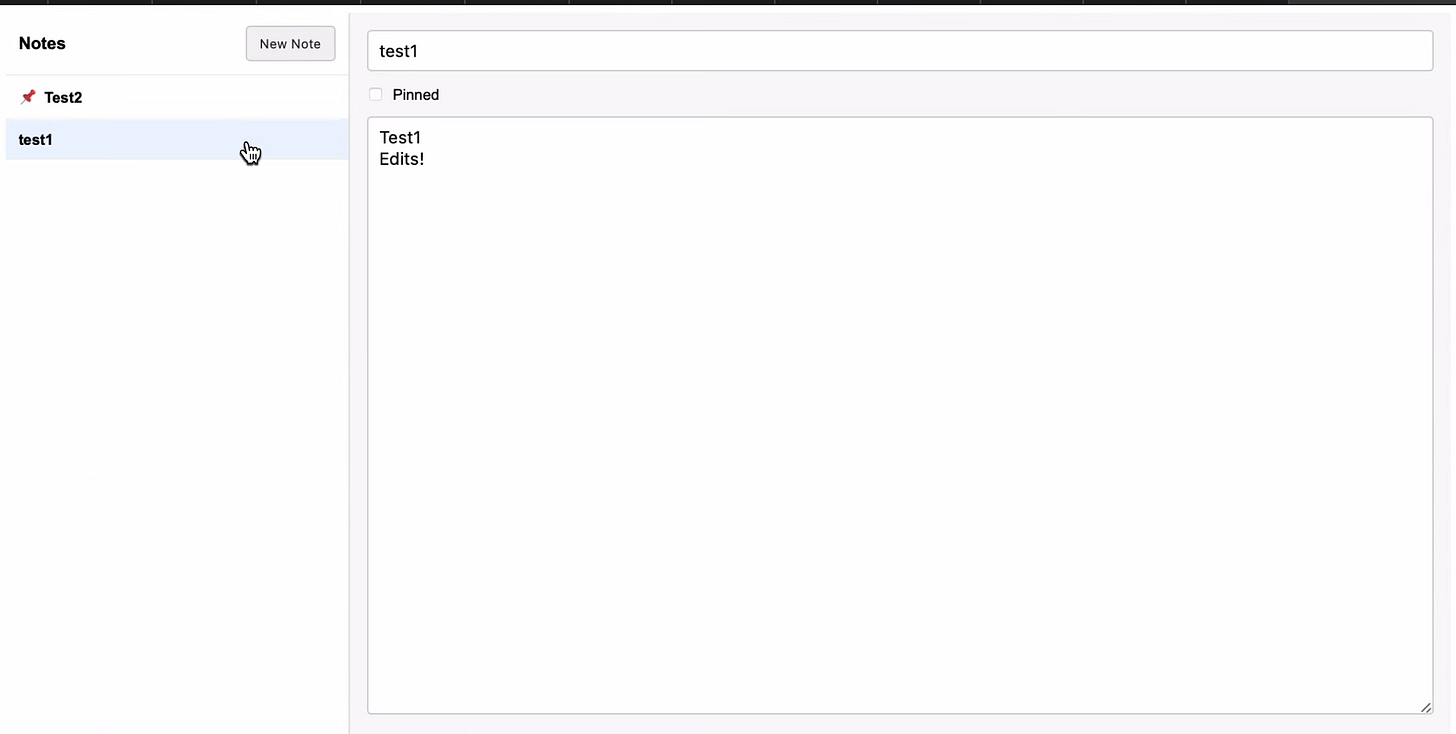

Tier 3

Tier 3’s prompt is significantly more prescriptive, including code snippets that explicitly define data structures.

At this point, the semantic space the prompt drives Codex into has a clearly defined idea of what an unstyled note-taking app should look like. The only unique UI features are superficial, such as where the “pinned” emoji appears on screen.

The note pinning feature has been common since tier 2 but appears in no tier 0 or 1 generations. The obvious explanation: tier 2’s prompt explicitly lists it as a requirement. Still, it’s interesting that the more creative early tiers never thought of pinning—another fairly standard feature in note-taking apps.

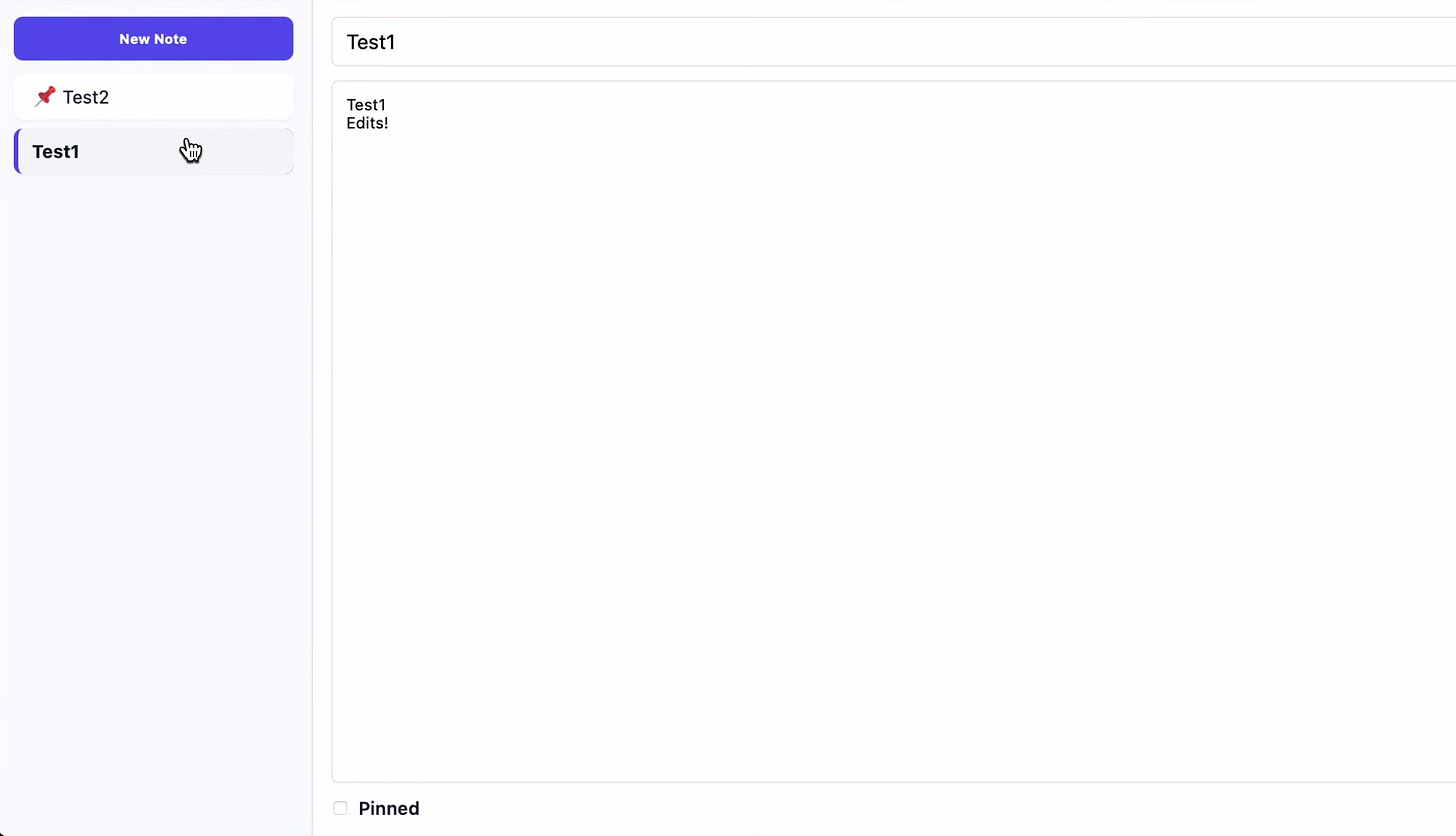

Tier 4

The final tier for this experiment is the first where the prompt is framed as a full PRD. If I ran this experiment again, I would place the prompt in a separate file to refer to as a PRD, rather than again just copy the text into Codex’s chatbot interface.

The UI is effectively fully converged between app version 1 and 2 at this tier. In this PRD, there is an instruction to “render the 2-column layout exactly.” Still, in my opinion there is still quite a bit of variation that could have been attempted that Codex doesn’t explore.

This is also the first tier where entire chunks of code in the most critical files are effectively identical. The specificity of the PRD was comprehensive enough that the generation process produced nearly the same code path through the model’s decision tree from beginning to end of files. Considering the vast number of possible token sequences available in Codex’s parameter space, achieving such consistent output through prompt engineering alone is noteworthy.

Next steps

One key lesson: every LLM output is probabilistic, but deviations between successive generations decrease as prompt specificity increases. This isn’t surprising, but it’s striking how visually obvious the pattern becomes when comparing just two generations from the same prompt.

Some other lessons are more interesting:

Adding too much constraint without sufficient guidance can introduce bugs or missing features in the generated code.

Without enough specificity, two apps from the same prompt won’t just look different—they’ll have different features and varying quality. This suggests the best code generation results come either from writing highly specific prompts or generating the same app multiple times and cherry-picking features from each version.

That last point brings us full circle: we’re beginning to appreciate the value of the wide variety of code generated by that roomful of infinite monkeys.

I’m interested in learning more about how different balances of creativity and determinism affect a codebase. For my next experiments, I plan to add features to an existing project while varying both the specificity of feature prompts and the availability of supporting context like API contracts.

Excellent analysis; what if the trade-off between fostering AI creativity for UI diversity and ensuring codebase determinism for production-level robustness becomes a core architectural challenge that fundamentally redefines our approach to agile development, particularlly in larger projects?