Feature creeps and web scrapers

At an architectural crossroads on an AI project using web data

One of the aspects of AI-assisted coding that I find most exciting is how it prioritizes architectural decision-making. As a developer, it's tempting to dive in headfirst, start coding, call it a PoC, and move on. You can fall into the same trap with AI code assistance by simply throwing prompts at the system to see what happens.

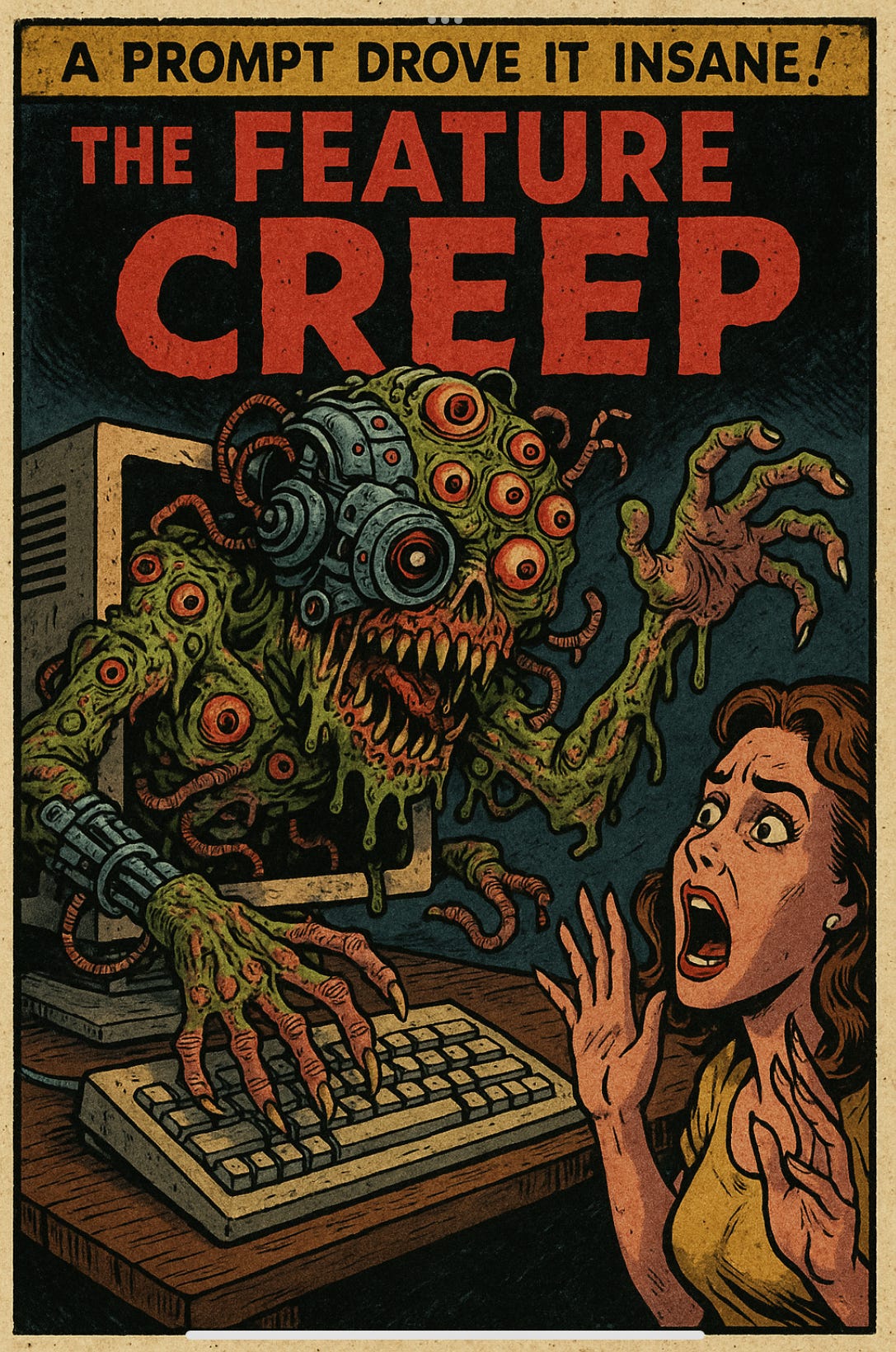

Of course, anyone who has tried this approach knows the result is typically an over-engineered, sputtering mutation of what you initially hoped to develop. Each increasingly desperate prompt to fix strange behavior only spawns new aberrations that require more frantic prompts until you eventually abandon the project in some forgotten GitHub repository. I suspect most people who've experimented with AI code tools have at least a few of these AI-conjured Feature Creeps locked away in digital basements. I certainly do.

Trying to ensure my new project doesn’t turn into a Feature Creep

My project relies on a curated dataset of music information available online. The eventual value of this project will depend on:

The relevance, accuracy, and freshness of the dataset

How accessible the data is to a frontend tool

This is fundamentally a data aggregation problem, where the tool increases the signal-to-noise ratio of dispersed or unwieldy information. For decades, websites have found success with data curation and aggregation:

Job listings on Indeed and [monster.com](http://monster.com), etc.

Air travel info on [kayak.com](http://kayak.com), Travelocity, etc.

News sites like Apple News

My system isn't trying to find visitors the cheapest plane ticket. I'm simply leveraging LLM creativity to generate cool music playlists. However, regardless of a project's scale or goals, careful architectural decisions remain critical, especially those affecting data ingest and curation.

First things first: how do I enable an LLM-powered agent to access the web and retrieve information?

How ChatGPT’s web search works

Anyone who has used chat interfaces like ChatGPT or Google Gemini has likely noticed the "searching the web" step that often appears after submitting a query. This standard feature exists across today's AI chat platforms. While it doesn't always guarantee accurate results, these web searches provide a degree of traceability since you can view the sources the AI used to formulate its response.

The LLM activates this web search tool whenever it determines your query requires internet-based information to answer properly. This capability was originally a standalone product called SearchGPT, which launched in 2024 before being integrated into ChatGPT.

Unfortunately, ChatGPT doesn't offer this web search tool through their developer APIs. Some other LLM providers like Anthropic and Google do offer ways to command their LLMs to search and summarize website information via APIs.

For this project, since I'm exclusively using ChatGPT's models and APIs, I needed to replicate the search function myself. This involves a two-step process: a script uses a tool to access web data, then feeds that information into ChatGPT's LLM for summary and processing.

Accessing web data respectfully

There are two primary approaches to retrieving data from web sources:

Using APIs provided by websites that offer official access to their data

Utilizing web scraping libraries for websites without accessible APIs

Before retrieving any information, it's crucial to review each website's terms of use. For sites with APIs like Wikipedia, these terms are clearly outlined in their documentation. The process typically involves creating login credentials, possibly paying for access, and then using the data within the established guidelines. It’s a straightforward engagement.

For websites requiring web scraping, determining permissible content access can be more challenging. Fortunately, many sites now include a "robots.txt" file specifically for web scraping agents. While robots.txt is a relatively recent development in web standards and its legal enforceability remains somewhat unclear, it provides essential guidelines for respectful site interaction that should be followed.

Robots.txt files inform agents (or humans reviewing the document) about:

Permitted scraping areas

Prohibited zones

Access rate limitations to prevent server overload

Site maps to help locate information efficiently

After developing initial music data, I used code assistant tools to create LLM-powered scripts for web access. My implementation prioritizes APIs when available and resorts to appropriate scraping techniques when necessary.

Now that I know how to access data, what do I do with it?

My project, in brief, helps visitors discover music recommendations through a backend agent that retrieves web-sourced music data. This agent creates playlists with creative sequencing based on song similarities and narrative qualities. The scripts mentioned earlier supply this web-sourced music data.

When designing a system reliant on web-sourced data, a key architectural decision is whether to store the dataset locally for the agent to access or have the agent perform fresh web searches each time—essentially, local versus network storage.

While I could build a proof of concept using either approach, my priority is finding the most cost-effective architecture that produces surprising and delightful results. If this tool isn’t fun to use, what’s the point?

Local vs. web data: cost considerations

Network access to music data with each visitor interaction requires agentic calls to APIs or web scraping tools, plus LLM summarization and information compilation. This web access must be well-structured with predetermined rules guiding the agent to the right information sources.

The main reason I consider this method less cost-effective than local storage is that visitors would likely request the same data repeatedly. Since the tool looks for relationships between songs, the LLM would need to search through content "live" each time. This creates enormous inefficiency in data compilation.

In contrast, a local relational database minimizes duplicate effort during data ingest. However, local access is only effective when the database contains all the necessary information for the LLM to create surprising and delightful playlists. Curating data so the LLM has everything it needs to generate truly surprising and entertaining playlists creates a form of "context anxiety,” which I talked about in a previous post. This is a concern that I suspect has existed since the dawn of databases.

Local vs. web data: quality considerations

AI offers developers powerful tools to discover and curate data through agentic workflows, streamlining every step from identification and ingestion to categorization and tagging. My current work focuses on fine-tuning these curation mechanisms. I'm exploring various approaches to help the LLM identify interconnected aspects of popular music in ways that are both flexible and substantive.

Despite these efforts, I can't shake the concern that my results might not surpass what you'd get by simply asking ChatGPT to list songs with specific attributes.

Data freshness presents another challenge with local storage. While it's obvious that new music releases require database updates, the contextual information around music also evolves over time. Artists give interviews revealing new insights about their songs. Awards and recognition can trigger reassessments of an artist's work and create new connections between established and emerging musicians. Capturing these subtle shifts is difficult, but it’s something you essentially get "for free" when your system performs real-time web searches with each user interaction.

Next steps in development

While I feel confident that a curated, local dataset providing an LLM with ‘Goldilocks’ context will unlock creativity in a way that’s far more scalable and cost effective than just diving into the web with every query, defining and maintaining the system architecture to actually do that curation remains a challenge for me. Hopefully I can keep the project on track and prevent the system from mutating into another Feature Creep.

There's a qualitative aspect to playlist output that's hard to test through automation. For now, I'll rely on manual comparison between what my curated dataset produces versus what ChatGPT casually spits out with a simple query. This will be the bedrock test case of my system testing. Hopefully I'll reach a point with this project where I can share it here for other people to test too, though I still have a ways to go. In the meantime, I'm hoping to write more articles in this series on some aspects of my database structure and how I'm using embeddings to coax the LLM toward unique and creative choices.