Exploring ChatGPT connectors

I used OpenAI’s new support for MCP to enable ChatGPT to scan for Bluetooth devices

In my last post, I mentioned that OpenAI recently opened up support to run apps “inside ChatGPT.” What this really means is that OpenAI now offers first-class support for MCP, similar to what Anthropic has offered for some time. This framing of app integration as “connectors” is more user-friendly and shows how OpenAI’s marketing and UI teams may have a better touch for non-enterprise markets.

The more I read about connector support opening up in the coming months, the more intrigued I became about how the system works. Just how hard would it be to create an MCP server and connect it to the ChatGPT chatbot?

I spent a few weeks developing an MCP server concept for debug instruments (link). For this project, I wanted to create something new for a ChatGPT interface while exploring how these web-first tools reach outside their chat interface to interact with the real world.

My goal for this ChatGPT-compatible MCP tool was simple: scan for Bluetooth Low Energy devices near the user. I wanted to open ChatGPT, type “what Bluetooth devices are nearby,” and get a list of names with rough proximity metrics.

Scanning for Bluetooth devices

Most people know Bluetooth from wireless headphones and car connectivity, but those devices use Bluetooth Classic. In 2010, the Bluetooth 4.0 specification introduced Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), a protocol designed for lower power consumption, simpler pairing, more flexible network topologies, and battery-powered IoT devices. Today, your keyboard, mouse, smartwatch, continuous glucose monitor, insulin pump, heart rate monitor, and billions of other devices support BLE.

A key feature of BLE is its advertising mechanism. BLE devices broadcast small data packets called advertisements on three dedicated channels in the 2.4 GHz ISM band. These advertisements serve two purposes: they can transmit small amounts of data directly to any listening scanner (commonly used by sensors and health monitors), or they can indicate that a device is available for connection. When a scanner detects a connectable advertisement, it can initiate a connection to establish a bidirectional channel with higher bandwidth and security.

Scanners can also estimate distance to an advertising device by measuring signal strength, called the Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI), measured in dBm. While RSSI provides only a rough distance estimate due to environmental interference, it’s useful for proximity detection.

This advertiser-scanner relationship is what I’ll be exploring with this MCP server. I want ChatGPT’s chatbot to interface with a server running locally on my machine that acts as a scanner for active Bluetooth advertisers, reporting back information from the advertisement payload and RSSI values.

I’d like to eventually build more sophisticated Bluetooth interactions, especially around spatial awareness derived from RSSI. But for now, I want to see how difficult it is to retrieve basic Bluetooth information.

Rube Goldberg’s LLM-powered Bluetooth scanner

All this “running apps inside chat” marketing is really an official process for connecting remote LLM-powered agents to tools and data through HTTP requests. I write a query locally, and the remote agent responds by calling remote MCP servers over the internet. Using additional context from those servers, the agent sends a response back to me through chat.

In this experiment, the MCP server runs locally on my Mac mini. It exposes a single tool that scans for Bluetooth LE advertisements for a set period, then responds with a list of discovered devices and all the information the scanner has learned about each one.

This is obviously a needlessly complex process, with data looping between local and remote endpoints just to scan for Bluetooth devices. You could easily handle this task locally using phone apps or operating system control panels. Nevertheless, I think this test hints at a trend we’ll see with agentic systems in the future.

But before we get into speculation, let’s look at how the experiment works. For those interested, the demo’s source code is available here:

Building the MCP Server

After iterating on a PRD for a Bluetooth Low Energy scanner wrapped by an MCP server, I used OpenAI’s Codex CLI to generate the project. My somewhat naive thought was that since Codex, ChatGPT, and the new SDK APIs to support “connector” MCPs all come from the same company, Codex might have the best chance of building a working system.

Interestingly, Codex’s questions suggested it had trouble finding the SDK documentation on OpenAI’s site. I had to point it in the right direction.

After that hiccup, Codex built the MCP server without much trouble, at least until I ran local test calls to retrieve nearby BLE device data. I spent time parsing through the JSON listing because some data seemed incorrect or missing. Through trial and error, the server eventually returned a reliable list of devices by name, address, and RSSI value. Once everything looked right, I exposed the server to the internet through ngrok and began trying to connect it to ChatGPT.

ChatGPT as MCP Client

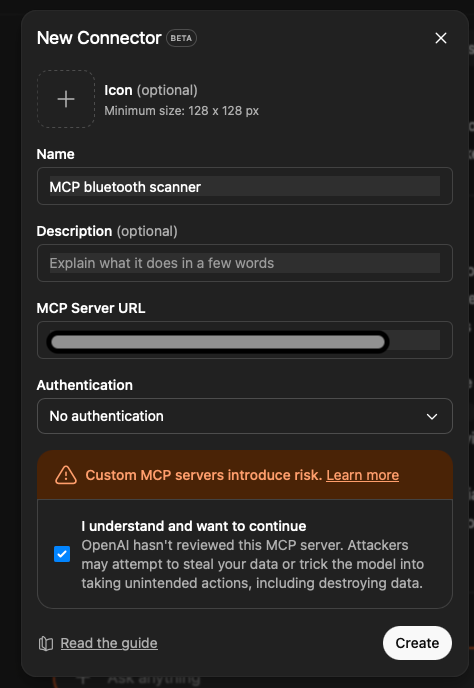

After switching ChatGPT to developer mode, I navigated to the Settings menu and found the New Connector screen where I entered the HTTPS server location and metadata. Clicking “Create” immediately triggered requests to my server, visible in my terminal. Success…except the calls failed and nothing worked.

An interesting sidenote: MCP as a standard relies heavily on natural language in its protocol. While tool declarations, command responses, and other data are expressed in JSON format, much of the information is provided in natural language. The only text in the codebase describing the “scan now” tool’s functionality to connecting clients (in this case, ChatGPT as the MCP client) is “Perform a one-shot Bluetooth LE scan and return discovered devices.” The AI must read and interpret this statement to determine when this tool might help respond to a query.

Even on its first attempt, this simple tool definition was enough for ChatGPT to understand that when I asked about BLE devices, it should try using this tool. The problem was that the tool wasn’t responding in a format ChatGPT expected.

Debugging became an iterative process of examining terminal output and ChatGPT responses, copying logs and taking screenshots to relay back to Codex. Codex eventually resolved all the bugs and delivered an MCP server that functioned as ChatGPT expected.

ChatGPT approved the server connection, and the chatbot could now scan for Bluetooth devices in my room whenever it determined that answering my prompts required such information.

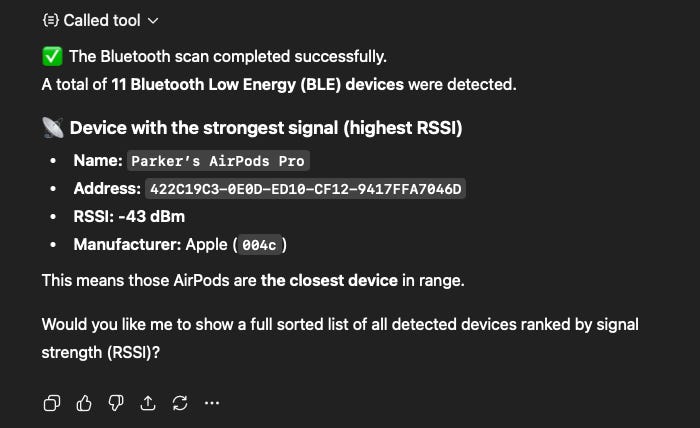

Seeing success with my first prompt, I wanted to see if ChatGPT understood the tool’s output to the point where it could interpret the data and provide meaningful insights. For this next experiment, I placed my AirPods case close to my Mac mini, so that the signal strength of the Bluetooth advertisements from the case should have relatively high RSSI.

Let’s take a step back and consider the LLM-powered agent’s reasoning process and sequence of actions. When I asked ChatGPT to identify the Bluetooth LE device with the highest RSSI near me, the agent had to: understand I was requesting Bluetooth information, check its available tools to confirm it could measure conditions in my physical proximity, call the server on my machine, identify my AirPods, and report that information back to me. This demo offers two interesting perspectives: its implications for user experience design, and what it reveals about LLMs’ ability to interact with the physical world.

The local execution advantage

While this demo takes a circuitous path through remote servers to perform a simple BLE scan, consider how different it would be with purely local LLM execution. Imagine asking your phone, computer, or smart home hub to help find your AirPods. A local LLM-driven agent could use available BLE scanners to detect and even triangulate the device’s location. With everything happening locally, security risks are minimized and response times are fast. The actual BLE scanning would be the slowest part of the process. This synthesis of real-world sensing, local inference, and natural language interaction represents the kind of intuitive human-machine interface that tech companies have been racing to deliver for years.

The broader implications of AI sensor access

It’s critical to consider the implications of MCP potentially providing AI systems with global-scale access to sensor data. The proliferation of Internet of Things devices across industrial, commercial, consumer, and even non-terrestrial environments means our world is increasingly instrumented with electronics. These devices continuously sense their surroundings, measuring temperature, acceleration, capturing images, detecting motion, and more, before transmitting their data across networks that could feasibly become accessible to AI through standardized protocols like MCP.

What observations, insights, and predictions could such a system make about the world and the people in it? The technological innovations most worth pursuing are those that, on balance, make us safer, healthier, happier, or wiser. AI has the potential to help us achieve these goals, but those of us in technology and regulatory fields must work together to ensure we gain more from this technology than we sacrifice in security, privacy, and autonomy.

Parker, I don't know what's up next on your list of topics, but I would love to hear about experiments with multi-agent teams. It would be really nice to see how a planner-coder-reviewer team can perform compared to a single agent, especially when it comes to iterations (reviewer talking back to planner). Obviously, to see the benefits you need at least a medium sized project, but I see you are not lack of those.

So if I understand well, the difference between this and the pin monitor mcp server is that the pin monitor uses localhost, while this needs a publicly available server. Is that correct?

(Btw, chatGPT says, if you use the chatGPT desktop app, you can use local MCP servers, so in this case it is only the model that remains remote. Too bad this concept does not work with the smartphone app.)